ARTIST BIO

EDUCATION

1982 Master of Fine Arts, California College of the Arts, Oakland, CA

1978-79 School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Tufts University, Boston, MA

1977 Ukrainian Studies (Summer Program), Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

1973 Bachelor of Arts, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ

1972 Brighton College of Education, Brighton, England, Exchange Program (Fall Term)

FELLOWSHIPS

1987 & 1984 Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Sweet Briar, VA

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

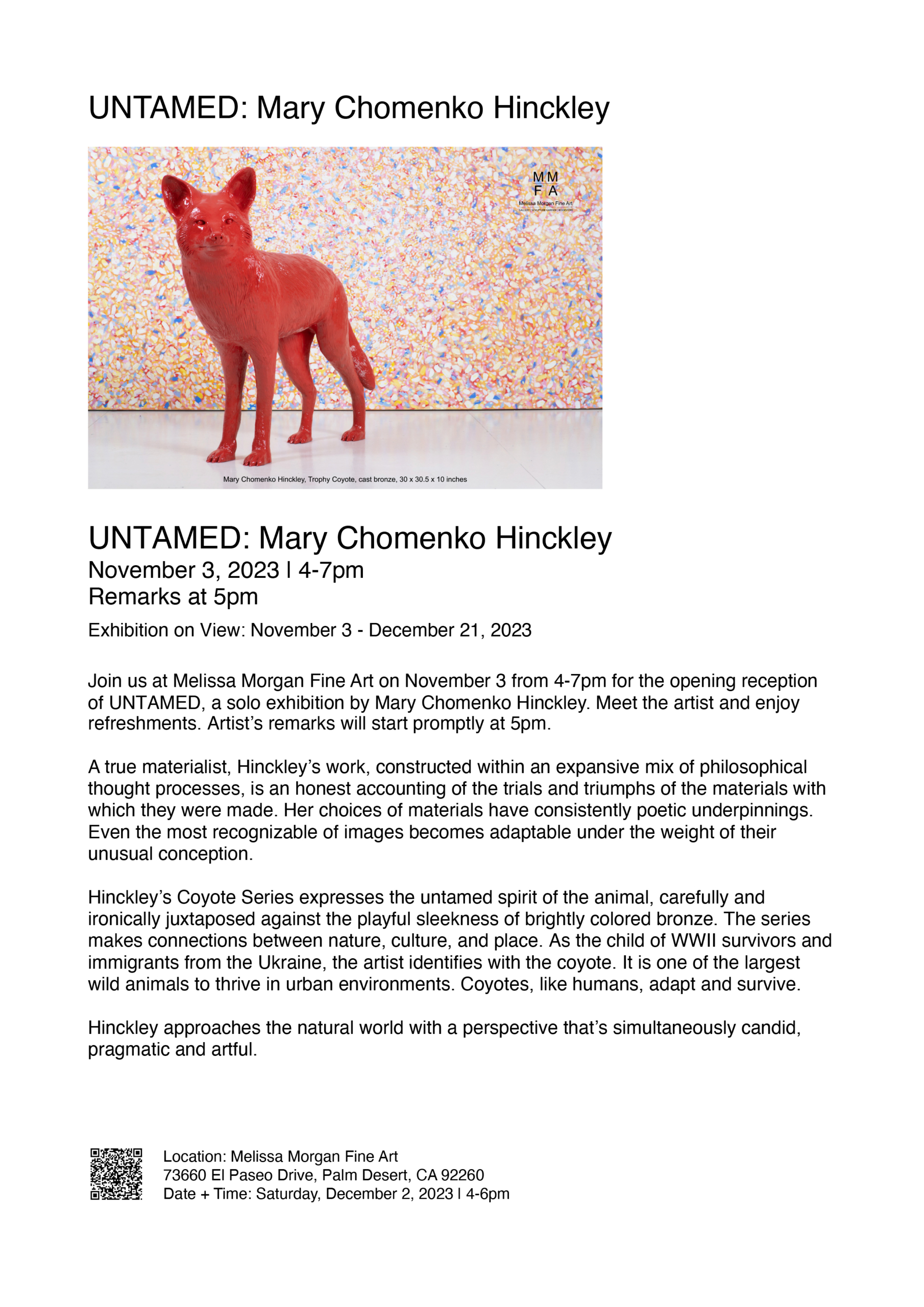

2023 UNTAMED: Mary Chomenko Hinckley, Melissa Morgan Fine Art, Palm Desert, CA

2020-2022 NW Upshur Artists’ Studio, Portland, OR

2021 Politics and Painting the Moment, NW Upshur Artist’s Studio, Portland, OR

2020 Pandemic Paintings. NW Upshur Artist’s Studio, Portland, OR

2018 Material Evolution: Paper, Paint, Patina. Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

2015 Material Evolution: Images and Objects – Urban Coyotes, Past and Present, Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

2013 Gates of Venice and Beyond: Studies in Color and Pattern, Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

2012 Birds in Morocco & Geometry: New Work in Glass, Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

2009 Rocks/Birds/Construction/Deconstruction, Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

2005 Jungle, Recent Photographs, Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

1996 Mary Chomenko: Sculptures & Carol Hake: Still Life Paintings, Los Altos Hills, Town Hall, Los Altos Hills

1992 Nature in Bronze, Ruth Bachofner Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

1989 New Work, Ruth Bachofner Gallery, Santa Monica, CA

1988 New Sculpture, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1988 Mary Chomenko, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Rental Gallery, San Francisco

1985 Mary Chomenko, Cast Paper and Bronze, and Beverly Daniloff: Paintings,

1985 James Turcotte Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1984 Works on Paper, Palo Alto Cultural Center, Palo Alto, CA

1984 C.A.D.R.E. (Computers in Art, Design, Research and Education), Palo Alto

1984 Civic Center, Palo Alto, CA, organized by San Jose State University (Cat.)

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2001-00 Artists Among Us, Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, Portland, OR

1997-94 Venice Art Walk, Venice, CA

1995 Women Confronting Issues of Aging, San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, San Jose, CA

1995 The Horse Show, Images of the Horse in Contemporary Art, Sylvia White, Santa Monica, CA and New York, NY

1993 Five Bay Area Sculptors, Harcourts Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1992 Metals Now, Downey Art Museum, Downey, CA

1991 Art-Over-the-Sofa, Boritzer/Gray Gallery, Santa Monica, CA (Jan Butterfield, Curator)

1991 From the Crucible, Recent Bronze Sculpture, Mary Chomenko, Sanford Decker & Don Treadway, Cerritos College, Fine Arts Gallery, Norwalk, CA

1991 Recent Classical Encounters, The IMC Gallery, Irvine, CA

1989 Five Bay Area Sculptors, Ianetti Lanzone Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1989 The Column in Art and Architecture, Pine Street Lobby Gallery, San Francisco, CA (Abram Garfield, Curator)

1989 Paintings by Sculptors and Sculptures by Painters, SEIPP Gallery, Castileja School, Palo Alto, CA

1989 Fine Arts in Metal Sculpture Exhibit, Pacific Grove Art Center, Pacific Grove, CA

1989 Women Working in Bronze, Fine Arts in Metal Gallery, San Jose, CA

1989 3Comm Corporation, Santa Clara, CA (Carol Dabb, Curator)

1988 The First Ten Years, S.F. MOMA Rental Gallery, San Francisco, CA (Marian Parmenter, Curator)

1988 Bay Area Bronze, Walnut Creek Civic Arts Center Gallery, Walnut Creek, CA (Carl Worth, Curator)

1988 Inanimate Animals, California Crafts Museum, San Francisco, CA (Ted Cohen, Curator)

1988 Annual Drawing Show, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1988 Not Your Usual Landscape Show, Lasori/Iri Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

1987 Gallery Artists, Inaugural Exhibit, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1986 Photography ’86 Invitational, Richmond Art Center, Richmond, CA (Robert Tomlinson, Curator)

1986 Fishow, Southern Exposure Gallery, San Francisco, CA (Elizabeth Raybee, Curator)

1985 Managerie, Animal Images by Contemporary Artist, San Francisco Airport, CA (Elsa Cameron, Curator)

1985 A Celebration of the Land, California State College, Stanislaus, CA (Dr. Hope B. Weness, Curator) Catalog

1985 Visual Dialogues of the Eighties/Dialogos Visuales de los Ochentas, San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, San Jose, CA and Galeria Metropolitana, Col. Roma, Mexico City, Mexico, (Erin Goodwin, Curator) Catalog

1984 Stars, Fuller Goldeen Gallery, San Francisco, CA

1983 Landscapes and Other Spaces, Clorox Corporation, Oakland, CA (Organized by PRO ARTS)

1983 San Francisco Art Festival, San Francisco, Art Institute and S.F. Civic Center, San Francisco, Ca

1983 Hayward Area Forum for the Arts, Civic Center, Hayward, CA (Jay DeFeo, Juror)

1983 The Northern California Regional Print Competition, Palo Alto Art Club Gallery, Palo Alto, CA

1983 California Women Artist, Matrix Gallery, Sacramento, CA

1982 Six on Paper, Smith Anderson Gallery, Palo Alto, CA

1982 Paper as Art/Art on Paper, The Storefront Museum, The Oakland Museum, Ca (Irena Barns, Curator)

1982 TECHSHOP ’83, International Sculpture Conference Instructors Exhibit, San Jose Institute of Contemporary art, Ca

1982 San Francisco Arts Festival, Moscone Center, San Francisco, Ca

1982 Group Exhibit, California College of Arts and Crafts, Artist’s Gallery, Oakland, CA1981 28th Annual Exhibition: Designer/Craftsman, Richmond Art Center, Richmond, CA

1980 California: Survey of Printmaking and Papermaking, Humboldt State University Arcata, CA

1979 Prints and Drawings, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

1979 Museum School Annual, Boston Center for the Arts, Boston, MA

1979 Women About Women, Cambridge Art Association, Boston, MA

1979 Visual Artists’ Union, New Members Show, Boston, MA

PUBLIC COMMISSIONS

2015 Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, Gift, Bronze Cross, Portland, OR 2006 OHSU (Oregon Health & Science University) Center for Women’s Health, Photograph Triptych, Portland, OR 1996 St. Bede’s Episcopal Church, Menlo Park, CA

1995 Christ Church Cross, Bronze Cross, Christ Church, Sausalito, CA

1992 Pasadena Coyote, One Colorado Associates, Old Town Pasadena, CA

1991 Agriculture, San Joaquin County, San Joaquin County Human Services Agency Building, Stockton, CA

1990 California Grizzly, California Arts Council, Ronald Reagan State Office Building, Los Angeles, CA

1988 Ocean Beach Fossil, The Arts Commission of San Francisco, The Great Highway Seawall Project, bronze medallion installed in pedestrian esplanade, completed 1989

AWARDS

1984 Claire N. Issacs Award, (Director of Cultural Affairs), San Francisco Arts Festival Artist of the Year, Nominee, one of eight emerging Bay area artists nominated by the Oakland Art Museum, CA

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Amerada Hess, New York, NY

Capital Group, Los Angeles, Ca

City of Palo Alto, CA

Clargro Corporation, New York, NY

Fannie Mae, Pasadena, CA

Intercontinental Hotels, San Diego, Ca

O’Melveny & Myers, Los Angeles, CA

Park Hyatt, San Francisco, CA

State of California, Ronald Regan State Building, Los Angeles, CA

Brobeck, Phleger & Harrison, San Francisco, CA

Chemical Bank, New York NY

City of San Francisco, CA

Digital Corporation, Pittsburgh, PA

IBM, San Jose, CA

Maui Land & Pineapple Co, Maui, HI

One Colorado Associates, Pasadena, CA

San Joaquin County, Human Services Bldg., CA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gallivan, Joseph, “Come on indoors; the viewing is fine,” Portland Tribune, Portland Life

Section B, p. 1 & 3 (illustrated)

Los Angeles Downtown News, January 21, 1991, Vol. 20, No. 3 pp. 1 & 16 (illustrated)

Martins, David C., AIA, “Art and Architecture.” Designers West, February 1990,

pp. 94 & 97 (illustrated)

Tamblyn, Christine, “Five Bay Area Sculptors,” Artnews, Nov. 1989, p. 177

“The Column in Art and Architecture,” (exhibition catalog) published by Community Arts, Inc.,

San Francisco, CA

Donohue, Marlena, “The Galleries,” The Los Angeles Times, February 24, 2989

Huneven, Michelle, “Cultural Assets,” LA Business, June 1988, pp. 40-41 (illustrated)

San Jose Mercury News, Extra Section #1January 8, 1986, p. 1 (illustrated)

“Here for the Children,” published by Oakland Children’s Hospital, 1986, p. 16 (Illustrated)

International Sculpture Magazine, June/July 1985, p. 24 (illustrated)

Werness, Dr. Hope B., A Celebration of the Land, published by California State College, Stanislaus. April 1985, pp. 23 & 29

Morris, Gay, “Computer Parts and Pretty Pastels, Peninsula Times Tribune, June 22, 1984, p. C-10

Wiley-Robertson, Salli, “Addressing Computers and Art,” Artweek, February 11, 1984, p. 13

Jan, Alfred, “Six on Paper,” Entertainment Review, January, 1984, p. 8

Goodwin, Erin, Visual Dialogues of the Eighties/Dialogos Visuales de Los Ochentas, published by San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art/Galeria Metropolitana, Mexico City, 1983, p. D-5

Newman, Nancy, C.A.D.R.E., (Computers in Art and Design, Research and Education) published by San Jose State University, December 1983, pp. 128-129

Winter, David, “People Who Live in Glass Houses,” The Peninsula Times Tribune, December 20, 1983, p. Dr

EDN Magazine, June 1983, pp. 5, 94, 127, 135, 149, 167 (illustrated)

Putnam, Sarah, “Images,” Boston Sojourner, May 1979

Gervich, Don, “Women Look at Women in New CCA Gallery,” Cambridge Chronicle, May 1979

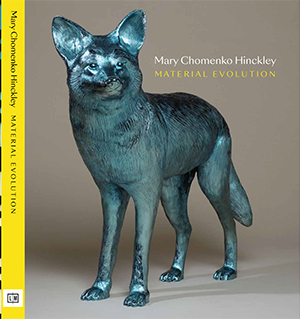

This exhibition coincides with the publication of my monograph MARY CHOMENKO HINCKLEY: MATERIAL EVOLUTION that spans 40 years of artistically resolving the perceived conflict between humans and the rest of creation. This new work continues to explore deconstruction of an image, the art making process analogous to travel and exploration and the conflict of wildlife and humans coexisting in our built world.

This exhibition coincides with the publication of my monograph MARY CHOMENKO HINCKLEY: MATERIAL EVOLUTION that spans 40 years of artistically resolving the perceived conflict between humans and the rest of creation. This new work continues to explore deconstruction of an image, the art making process analogous to travel and exploration and the conflict of wildlife and humans coexisting in our built world.